Battery Electric Or Hydrogen Fuel Cell Vehicles? Where do we go from here?

Stories authored with the Help of Designfruit AI

Why This Matters Now

As governments commit billions to hydrogen infrastructure and automakers bet on competing technologies, a fundamental question emerges: In a future powered primarily by renewable electricity - especially solar - does hydrogen for transportation still make sense?

With over 17 million electric vehicles sold globally in 2024 and roughly 1,160 hydrogen stations serving a few thousand fuel cell vehicles, the market has spoken clearly. But the story isn't over. Let's examine whether hydrogen has a strategic role, or if it's an expensive detour on the path to clean transport.

The Technologies: A Quick Primer

Battery Electric Vehicles (BEVs) store electricity directly in lithium-ion battery packs. Solar panels or grid power charges the batteries, which feed electric motors. Range: 250-400+ miles. Charging: 20-45 minutes (fast charging) to overnight (home charging).

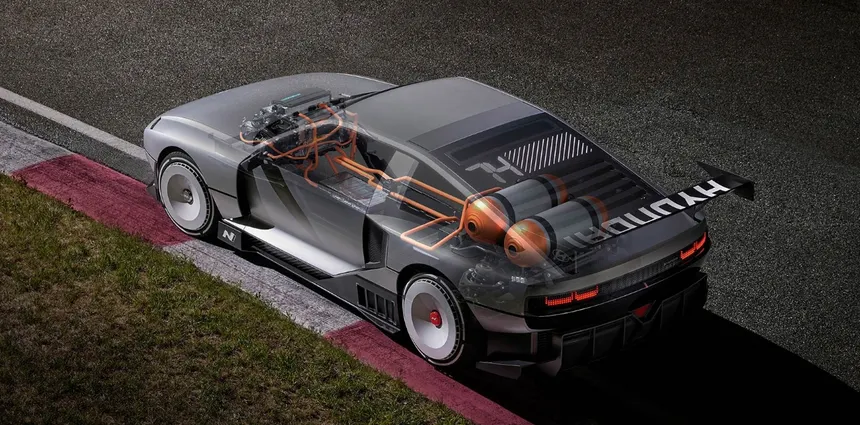

Hydrogen Fuel Cell Electric Vehicles (FCEVs) store compressed hydrogen gas at 700 bar pressure. A fuel cell stack converts hydrogen and oxygen into electricity, powering electric motors and emitting only water vapor. Range: 300-400 miles. Refueling: 3-5 minutes.

The critical difference? Both use electricity. BEVs use it directly; FCEVs use it to create hydrogen first.

The Efficiency Insight

Here's where the fundamental challenge emerges. Let's trace 100 kWh of solar electricity through each pathway:

Battery Electric Route

- Solar panels → 100 kWh generated

- Grid transmission → 95 kWh delivered (5% loss)

- Battery charging → 90 kWh stored (5% loss)

- Battery discharge to motor → 81 kWh used for motion (10% loss)

- Overall efficiency: 81%

A typical EV consuming 0.25 kWh/mile travels 324 miles from our original 100 kWh.

Hydrogen Fuel Cell Route

- Solar panels → 100 kWh generated

- Electrolysis → 60 kWh of hydrogen energy (40% loss)

- Compression to 700 bar → 54 kWh (10% loss)

- Transport & storage → 51 kWh (5% loss)

- Fuel cell conversion → 28 kWh electricity (45% loss)

- Electric motor → 25 kWh used for motion (10% loss)

- Overall efficiency: 25%

An FCEV with similar consumption travels just 100 miles from the same 100 kWh.

The verdict: For every mile an FCEV travels, a BEV could travel 3.2 miles using the same solar electricity. This isn't a small engineering gap - it's a fundamental thermodynamic reality.

The Current State: Infrastructure and Adoption

| Metric | Battery EVs | Hydrogen FCEVs |

|---|---|---|

| Global vehicle sales (2024) | 17 million | ~15,000 |

| Refueling/charging infrastructure | 5+ million stations | ~1,160 stations |

| Models available | 500+ models | 3 major models |

| Home refueling option | Yes (Level 2 charger: $500-2,000) | No (home electrolysis: $50,000-100,000+) |

| Fuel cost per mile (USD) | $0.05-0.10 | $0.15-0.30 |

| Refueling time | 20-45 min (fast) / 8 hrs (home) | 3-5 minutes |

The infrastructure gap tells the story. California - the most hydrogen-friendly US state - has roughly 60 hydrogen stations serving about 12,000 FCEVs, while supporting over 1 million BEVs with thousands of charging points.

Real-World Cost Comparison: 10-Year Total Ownership

Let's compare two similar vehicles over 150,000 miles:

Tesla Model 3 Long Range (BEV)

- Purchase price: $47,000

- Electricity (avg US rates): $4,500

- Maintenance: $6,000

- Total: $57,500

- Purchase price: $50,000

- Hydrogen fuel: $27,000

- Maintenance: $5,000

- Total: $82,000

With home solar charging (25-30% of generation surplus after home use):

- BEV electricity cost: $1,500

- BEV total: $54,500

The hydrogen fuel cost alone exceeds the entire 10-year operating cost of a solar-charged BEV.

The Solar Maxxing Scenario: When Abundant Clean Electricity Changes Everything

Now consider a future where humanity has maximized solar electricity deployment—rooftop arrays blanket suburbs, solar farms span deserts, and floating panels cover reservoirs. Global electricity generation is 70-90% renewable, predominantly solar. This isn't fantasy: the IEA projects solar to become the world's largest power source by the 2030s.

In this solar-abundant future, hydrogen's value proposition collapses for most transportation:

The Direct Use Advantage

When you have abundant, cheap solar electricity, using it directly in BEVs is simply superior:

- No conversion losses: That 100 kWh of solar electricity drives an EV 324 miles instead of an FCEV's 100 miles

- Lower infrastructure costs: Charging stations are simpler and cheaper than hydrogen production, compression, storage, and dispensing facilities

- Grid storage synergy: Parked EVs with bidirectional charging can stabilize the grid, storing excess solar during the day and feeding it back during peak evening demand

- Scalability: Every parking spot can become a charging point; hydrogen requires specialized stations

The Economic Reality

In a solar-maxxed world, electricity becomes progressively cheaper during peak production hours. This amplifies BEV advantages:

- Near-zero marginal cost: Solar electricity at 2-3 cents/kWh makes BEV fuel costs negligible

- Smart charging optimization: Vehicles automatically charge when solar generation peaks, maximizing use of abundant clean power

- Home energy integration: A residential solar system ($15,000-25,000) powers both house and car; home hydrogen production remains prohibitively expensive

The question becomes stark: Why convert cheap solar electricity into expensive hydrogen when vehicles can use that electricity directly?

Carbon Footprint in a Solar-Powered Grid

Let's examine lifecycle emissions in this scenario:

BEV powered by solar-heavy grid:

- Manufacturing: 8-12 tons CO₂

- Electricity (150,000 miles): 2-5 tons CO₂

- Total: 10-17 tons CO₂

FCEV powered by green hydrogen (from solar):

- Manufacturing: 10-14 tons CO₂

- Hydrogen production & delivery: 12-18 tons CO₂

- Total: 22-32 tons CO₂

Even when both use solar-derived energy, the FCEV produces 50-80% more lifecycle emissions due to the inefficient conversion process requiring more panels, more mining for electrolyzer materials, and more infrastructure.

In a solar-maxxed civilization, BEVs become the near-zero carbon option, while FCEVs become questionable on both efficiency and environmental grounds.

But Wait—What About Hydrogen's Advantages?

Let's be fair. Hydrogen advocates point to real benefits:

Refueling Speed

The claim: 3-5 minutes vs. 20-45 minutes matters for commercial fleets and long-haul drivers.

The reality: Fast charging technology is advancing rapidly. 2025 breakthroughs demonstrate 10-80% charging in under 10 minutes at 500 kW rates, with 800V architectures becoming standard. Tesla's V4 Superchargers hit 80% in 25-30 minutes today. By 2028, solid-state batteries may enable 5-minute charges.

For the 90% of driving that's local commuting, overnight home charging eliminates "refueling" entirely—a convenience hydrogen can't match.

Cold Weather Performance

The claim: FCEVs don't lose 20-40% range in freezing temperatures like BEVs.

The reality: Newer EVs with heat pump technology reduce winter range loss to 10-20%. Preconditioning while plugged in eliminates most cold-start issues. More importantly, in a solar-maxxed future with cheap electricity, "wasted" energy becomes less economically significant.

Weight and Payload

The claim: Hydrogen tanks (400-500 lbs) are lighter than equivalent-range batteries (900-1,200 lbs), critical for trucks and aircraft.

The reality: For passenger cars, the weight difference is marginal:

- Tesla Model 3: 3,800 lbs

- Toyota Mirai: 3,100-3,300 lbs

For long-haul trucks, this becomes more relevant—battery-electric semi trucks sacrifice 2-4 tons of payload capacity. Here, hydrogen has genuine advantages.

Where Hydrogen Actually Makes Sense

In a solar-abundant future, hydrogen isn't worthless—it's just specialized:

Aviation

Why hydrogen wins: Batteries remain too heavy for long-haul flight. A Boeing 787 needs roughly 100 tons of jet fuel for a 7,500-mile flight. Equivalent batteries would weigh 400+ tons; liquid hydrogen just 35 tons.

The challenge: Cryogenic storage (-253°C), new aircraft designs, and airport infrastructure. But for eliminating aviation's 2.5% of global emissions, hydrogen is likely the only viable path.

Transoceanic Shipping

Why hydrogen wins: Large container ships need 100-200 MWh daily—far beyond practical battery capacity. Onboard solar panels can power auxiliary systems but not main propulsion for vessels requiring 20-50 MW continuous power.

The solution: Hydrogen or ammonia (a hydrogen carrier) enables zero-emission cargo shipping, though port infrastructure remains nascent.

Long-Haul Heavy Trucking (Maybe)

Why hydrogen might win: 800+ mile ranges with 5-minute refueling suits logistics operations. Weight savings increase payload capacity.

Why BEVs might win anyway: Battery swap stations (90 seconds) and megawatt charging (80% in 15 minutes) could match hydrogen's convenience while keeping superior efficiency.

The verdict: This sector remains genuinely competitive, likely splitting based on route profiles and regional infrastructure.

Industrial Processes and Grid Storage

Why hydrogen wins: Steel production, chemical manufacturing, and seasonal energy storage need hydrogen as a feedstock or energy carrier—uses where efficiency matters less than storage duration or high-temperature heat.

The Cost Trajectory: Can Hydrogen Catch Up?

Current green hydrogen costs: $5-10/kg Target for competitiveness: $1-2/kg

The U.S. Department of Energy projects $1/kg by 2030 with massive scale-up. But here's the problem: solar electricity is also getting cheaper. Even if green hydrogen reaches $1/kg, it still costs 3x more per mile than direct electricity use.

The efficiency penalty is permanent. No technological breakthrough makes electrolysis, compression, and fuel cells more efficient than using electricity directly. Physics sets the limit.

What Could Change This Analysis?

Breakthroughs That Could Favor Hydrogen:

- Solid-state hydrogen storage at room temperature and pressure (eliminates compression costs)

- Direct solar-to-hydrogen technology bypassing electrolysis losses (theoretical, not yet viable)

- Hydrogen infrastructure mandates by governments making FCEV fueling as convenient as EV charging

- Battery technology plateau where energy density stops improving

Breakthroughs That Would Further Favor BEVs:

- Solid-state batteries (10-minute full charges, 500+ mile ranges by 2028-2030)

- Grid-scale storage solving solar intermittency, making constant cheap electricity available

- Wireless charging roads enabling infinite-range EVs in urban areas

- Battery recycling closing the loop on materials, eliminating mining concerns

Comparison of Popular FCEV and EV Models (2025)

Below is a detailed comparison between the most popular Fuel Cell Electric Vehicle (FCEV) models and Battery Electric Vehicle (EV) models as of 2025. Data is based on manufacturer specifications, EPA estimates, and industry reports. FCEVs like the Toyota Mirai and Hyundai Nexo remain niche with limited sales (~13,000 globally in 2024), while EVs dominate with over 17 million sold in 2024, led by Tesla models.

Key notes:

- Pricing: Starting MSRP (US dollars, including destination fees where applicable).

- Range: EPA-estimated driving range on a full tank/charge.

- Acceleration: 0-60 mph time.

- Maintenance: Estimated 5-year costs (based on averages; EVs generally lower due to fewer moving parts, ~$3,000–$6,000; FCEVs higher due to fuel cell complexity, ~$5,000–$8,000).

- Fuel Cost: Per-mile estimate (EVs: ~$0.05–$0.10 at average US electricity rates; FCEVs: ~$0.15–$0.30 at $5–10/kg hydrogen).

- Other Factors: Infrastructure availability, efficiency, and environmental notes.

Popular FCEV Models

| Model | Starting Price | EPA Range | 0-60 mph | 5-Year Maintenance Est. | Fuel Cost per Mile |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Toyota Mirai | $51,795 | 402 miles | ~9.2 sec | ~$5,000 (similar to EVs, but fuel cell inspections) | $0.15–$0.25 |

| Hyundai Nexo | $61,470 | 380 miles | ~9.5 sec | ~$6,000 (includes free hydrogen up to $15,000/3 years) | $0.15–$0.30 |

| Honda CR-V e:FCEV | ~$50,000 (est.) | ~270 miles (plug-in hybrid mode) | ~8.5 sec (est.) | ~$5,500 | $0.15–$0.25 |

Popular EV Models

| Model | Starting Price | EPA Range | 0-60 mph | 5-Year Maintenance Est. | Fuel Cost per Mile |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tesla Model Y | $46,630 | 327 miles (Long Range) | 4.6 sec | ~$3,000–$4,000 (low; over-the-air updates) | $0.05–$0.10 |

| Tesla Model 3 | $42,490 | 321 miles | 4.1 sec (Performance) | ~$3,000 (minimal; battery warranty 8 years) | $0.05–$0.10 |

| Ford Mustang Mach-E | $41,995 | 300 miles (extended-range) | 3.5 sec (GT) | ~$4,000–$5,000 | $0.05–$0.10 |

| Chevrolet Bolt EV | $28,595 (2027 model; 2025 similar) | 255–259 miles | ~6.5 sec | ~$3,500 (affordable parts) | $0.05–$0.10 |

Overall Comparison Insights

- Pricing: EVs start lower (e.g., Bolt at ~$29k) and offer more variety; FCEVs are premium-priced due to tech complexity.

- Range & Performance: Comparable ranges, but EVs accelerate faster in performance trims; FCEVs excel in cold weather (no 20–40% loss).

- Maintenance: EVs cheaper overall (no oil changes, regenerative braking); FCEVs may require specialized service for fuel cells, potentially 50–100% higher per reports on fleets.

- Fueling: FCEVs refuel in 3–5 min but limited stations; EVs charge in 20–60 min (or overnight at home) with widespread infrastructure.

- Efficiency & Environment: EVs 70–90% efficient; FCEVs 25–40% (losses in hydrogen production); both zero tailpipe, but EVs cleaner on solar grids.

- Adoption: EVs outsell FCEVs 1,000:1; FCEVs niche for fleets/trucks where quick refuel matters.

Data sourced from manufacturer sites (Toyota, Hyundai, Tesla, Ford, Chevrolet), EPA, IEA reports, and industry analyses as of October 2025. Prices/ranges may vary by trim/region; check incentives (e.g., $7,500 US EV tax credit).

The Verdict: Context Is Everything

For 90-95% of passenger transportation: Battery EVs win decisively. They're more efficient, cheaper to operate, supported by vastly more infrastructure, and integrate seamlessly with home solar. In a future with abundant solar electricity, this advantage only grows.

For aviation and transoceanic shipping: Hydrogen (or derivatives like ammonia and synthetic fuels) is the only realistic zero-emission path.

For long-haul trucking: The battleground remains open, with the winner determined by infrastructure development and charging speed breakthroughs over the next 5 years.

For industrial and chemical processes: Hydrogen is essential, not as transportation fuel but as a chemical input and industrial heat source.

Conclusion

Here's the fundamental insight: Hydrogen isn't really an alternative to oil—it's electricity in disguise. Every hydrogen vehicle is actually an electric vehicle with extra steps.

In a world transitioning to solar-powered electricity grids, those extra steps become increasingly hard to justify for most transportation. The 60-70% energy loss from converting abundant solar electricity to hydrogen, then back to electricity, looks less like innovation and more like inefficiency.

The future isn't binary. Battery EVs will dominate personal and urban transportation. Hydrogen will enable aviation and heavy maritime shipping. Both technologies serve clean transport—but in fundamentally different roles.

The question isn't "hydrogen vs. electric." It's "direct electricity vs. electricity-via-hydrogen"—and for most ground transportation, cutting out the middleman makes economic, environmental, and practical sense.

Current infrastructure snapshot: 5 million+ EV charging points globally; ~1,160 hydrogen refueling stations. Investment trajectory: $500+ billion in EV infrastructure by 2030; $100 billion in hydrogen infrastructure. The market is placing its bets.

Did I miss Something? What do you think? Tell me in the Comments Section below.

Sources

Department of Energy

Trends in electric car markets – Global EV Outlook 2025 – Analysis - IEA

Over 1,000 Hydrogen Refuelling Stations Worldwide in 2024

Electric Vehicle Myths | US EPA

Department of Energy

Electric vehicle charging – Global EV Outlook 2025 – Analysis - IEA

caranddriver.com

caranddriver.com

IEA: Solar PV To Drive 80% Of Renewables Growth By 2030

Tesla launches first full V4 Supercharger station with 500 kW capacity | Electrek

patentpc.com

Hydrogen | Airbus

Electric Vehicle Outlook | BloombergNEF

Hydrogen: Investment in the Energy Transition - FCHEA

Comments (0)

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!